A Trans-historical Decolonial Window

Ana Paula dos Santos at Stadt der Fotografinnen. Frankfurt 1844-2024

“ The window symbolizes change, a place of observation, perhaps a stage.”

— Ana Paula dos Santos

Ana Paula dos Santos, Series ‘Minds thirsty for justice’ - Black Lives Matter protests: Rally at Hauptwache, black-and-white on Glicée print, Frankfurt am Main 2020, HMF.Ph38649. Image courtesy of the artist and Historical Museum, Frankfurt

The medium of photography in Ana Paula dos Santos's work speaks for itself, much like her own identity—a Latina Black female artist. If we humorously created a chart to categorize levels of privilege in the present world, akin to the chart of MBTI personality test, based on criteria such as gender, skin color, and nationality, Ana Paula would clearly fall into one of the most neglected groups. Whether it pertains to women, Black individuals, or Latinas, Ana Paula is an almost perfect representation of racialized bodies in today's society. She once recounted a story with a bit of humor involving a conversation with a white European man: "He told me that his Plan A never fails. How could he imagine that I need to prepare plan B, C, D, E, F, G...?" This comparison might be a bit extreme, but I find it exemplify very well the uptodate unbalanced distribution of social resources among different groups.

As the only photographer and artist who was neither born nor raised in Germany, but has been living there for over ten years, Ana Paula's participation in the exhibition Stadt der Fotografinnen (City of Women Photographers) holds equivalent significance for the city of Frankfurt am Main as The Other Story, curated by Rasheed Araeen in the late 1980s, did for British contemporary art. It stands as a monument marking the progressive stage of decolonization and a reemphasis on the definition of citizenship.

Ana Paula dos Santos, Series ‘Minds thirsty for justice’ - Black Lives Matter protests: Rally at Hauptwache, black-and-white on Glicée print, Frankfurt am Main 2020, HMF.Ph38649. Image courtesy of the artist and Historical Museum, Frankfurt

Minds Thirsty for Justice is a work that first caught my eye with its notable division marked by the different exposure values on either side. The left side is noticeably darker than the right. At first glance, it appears to be a documentary photograph, capturing a scene from the Frankfurt Black Lives Matter movement initiated by ISD (Initiative Schwarze Menschen in Deutschland) in 2020. This movement was primarily sparked by the global outrage over the killing of George Floyd by a police officer in Minneapolis, USA, on May 25, 2020, as well as the racially motivated murders in Hanau on February 19, 2020. The ISD group, with which the artist Ana Paula is in close contact, was founded in 1985 and advocates for justice for Black people. At the scene outside the Hauptwache subway station, some members are holding a large black fabric sign with white text in both English and German “Black Lives Matter, Stoppt rassistische Polizeigewalt jetzt!” (Black Lives Matter, stop police violence now). By raising the emerging issues of racial discrimination and police misconduct within Germany, this movement has brought attention to the experiences of Black people and other minorities in the country.

The photographs are of low resolution and out of focus, which makes them more artistic rather than documentary. The lack of focus downplays the event and narrative within the photo, drawing my attention instead to the contrast between black and white. The darker left side and the lighter right side remind me of the symbolism of Yin and Yang, as well as Hilma af Klint’s painting series The Swan, both of which present an unification of opposites. There is black within white, white within black. The divided black and white are in a state of fluidity, similar to the presence of tangible color in Minds Thirsty for Justice. The blurred narrative in the historical moment becomes a canvas to demonstrate this fluidity of division and how fragile terms like “black” or “white” can be.

Ana Paula dos Santos, Series ‘Minds thirsty for justice’ - Black Lives Matter protests: Rally at Hauptwache, black-and-white on Glicée print, Frankfurt am Main 2020, HMF.Ph38649. Image courtesy of the artist and Historical Museum, Frankfurt

Hilma af Klint 'Group IX/SUW, The swan, no 1' 1914-15. Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation, HaK149. Photo: The Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden

The color black becomes an extension of the artist’s own identity in Ana Paula’s work. Hence “black and white” no longer serves just as a color entity. Instead, it is encoded with symbolic meaning, highlighting the division of any terms in contradiction. This duality underscores contrasts such as “Dark” and “Light,” “Female” and “Male,” “East” and “West,” or anything else that comes to mind when thinking of contradiction or division. Every pixel in Ana Paula’s black and white analog becomes an empty space onto which the viewer’s cognition can be projected. I primarily project this contrast as “Self” and “Other.”

As a method of examining the psychology of the colonialist mindset, Richard Morrock illustrates four tactics of divide and rule practiced by Western colonialists:

1. The creation of difference within the conquered population,

2. The augmentation of existing differences,

3. The channeling of exploitation of these differences for the benefit of the colonial power

4. The politicization of these differences so that they carry over into the post-colonial period.(1)

Throughout these tactics of Richard Morrock, the word "differences" is repeatedly articulated. The notion of division is majorly contributed by individualism as well as the language system we are applying for constructing human civilisation. Noson S. Yanofsky has mentioned that the human language is a product created subject to contradictions. And in fact even physical objects don’t have sharp divisions(2). Same as for humans, nobody is completely separated from the whole. I perceive individualism as a methodology for developing self-consciousness. However, it is crucial to remember that this process of self-discovery is not the ultimate goal. “Our sense of self is an essential ingredient to our success as a species. Maintaining a self-identity means we can tie together a coherent set of memories, helping us to perform better based on past experiences…Science now confirms with certainty that our sense of isolated individuality is a subjective illusion, a projection maintained through the evolved architecture of the brain. It seems, increasingly, however, to be a harmful one in the modern globalized context, at least when pushed to excess in combination with our modern culture” (3).

As illustrated in Ana Paula's work, photographs are unclear and undefined. The lighting, exposure, and contrast, which create black and white tones, are easily manipulated by the artist, both when taking the photo and in the darkroom. The outcome can be altered just as easily as our perceptions can change. As explained in the I Ching (also known as Book of Changes and Yijing), “the only thing that never changes is change itself”(4). Instead of fixating on what is black and what is white, perhaps we can learn to put less weight on these terms and definitions and pay more attention to the fluidity and potential for variation inherent in the process itself, much like how Ana Paula plays with the value of exposures in her photography.

I like to use this metaphor: “Being a person who works in culture and art is like an old grandma who picks up wasted cartons and empty bottles—the abandoned materials of the city, the neglected elements of human narrative.” This metaphor underscores the opportunity for self-reflection on humanity during a creative process. Ana Paula's identity as "Black," "female," and "Latina" are elements that have been neglected in the past decades, even centuries. Now, they have become the "treasures" of artistic creation. It is complex to determine whether this identity brings the artist more opportunity or more tragedy in the present day. Events unfold without a reasonable explanation. An individual can probably only feel and experience what has been given and react to it within one’s capacity. Ana Paula chooses to respond to her surroundings proactively, not minding a certain amount of aggression. She appears to me as a well-armed warrior in this decolonial manifestation. Her armour is woven from her life experiences as a Black Latina from the city of Santos in Brazil on her journey to Santiago de Chile and Frankfurt am Main in Germany. The exhibition Stadt der Fotografinnen (City of Women Photographers) is one of her victories.

“Brazil is indeed the biggest Afro diaspora country in the world. On a beach like this in Brazil, you can go surfing, enjoy the sunlight only if you have a universal body. As a Black person, the sun can turn you ‘darker,’ and the darker you are, the stronger the racism there would be.”

— Ana Paula dos Santos

Ana Paula dos Santos, Series ‘Deconstructing a Place in the Sun, 2015-2018 / Historical disturbance, 2020, Exhibition view Stadt der Fotografinnen, Frankfurt am Main, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist.

Patience is necessary for reading Ana Paula’s work, because they have never been seeking viewers' attention. In fact, it’s never been her intention to please anyone, which is evident from the rough and unpolished textures in her works. Deconstructing a Place in the Sun is a good example of this approach. Sociologist Eric Otieno Sumba interviewed Ana Paula back in 2020(5), when Ana Paula has mentioned that the term “A place in the Sun” brought up by Bernhard von Bülow is one vital factor that inspired her to create this series. Bernhard von Bülow, the former minister of the German Empire said before the outbreak of World War I “We do not want to put anyone in the shade, but we also demand a place in the sun,” marking southwest Africa and Kiautschou Bay in China as the German colonial destination. The title of Ana Paula’s series Deconstructing a Place in The Sun directly indicates the artist's goal of reexamining the colonial history of the German Empire. The series of photographs is placed together with the installation Historical disturbance, a foldable beach chair, and an inflatable balloon, both covered with graffiti in black spray paint done by the artist, suggesting a silent rebellion against leisure. The photo works Deconstructing a Place in The Sun depict beach scenes from her hometown, the port city of Santos in Brazil, an ideal vacation destination. However, the almost twilight-like tones diminish the joy of a sunny beach scene in our collective memories, rendering the tropical paradise at the Brazilian beach unappealing. Even though there are palm trees and a clear sky, I feel freezing sadness at the same time. This deconstruction of the stereotypical sunny beach day is intentionally done by the artist. Leisure and entertainment often obscure historical memories, allowing parts of history to be easily forgotten.

Ana Paula dos Santos, Untitled (Deconstructing a Place in the Sun), Giclée print, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist and Sakhile&Me

“There was no other way to enter, it was the coast, from one coast to another coast…”

— Ana Paula dos Santos

When people are relaxing on the beach, it is easy for them to forget that this part of the land connected to the ocean was also the entry point for colonizers arriving in South America in the 15th century. By tracing back the memory of the colonial beginnings of Brazil, Ana Paula intentionally peeled off the outer layer of a tropical Brazilian beach. This allows us to recognize that a sunny day can also be melancholic and that the unpleasant parts of history need to be commemorated.

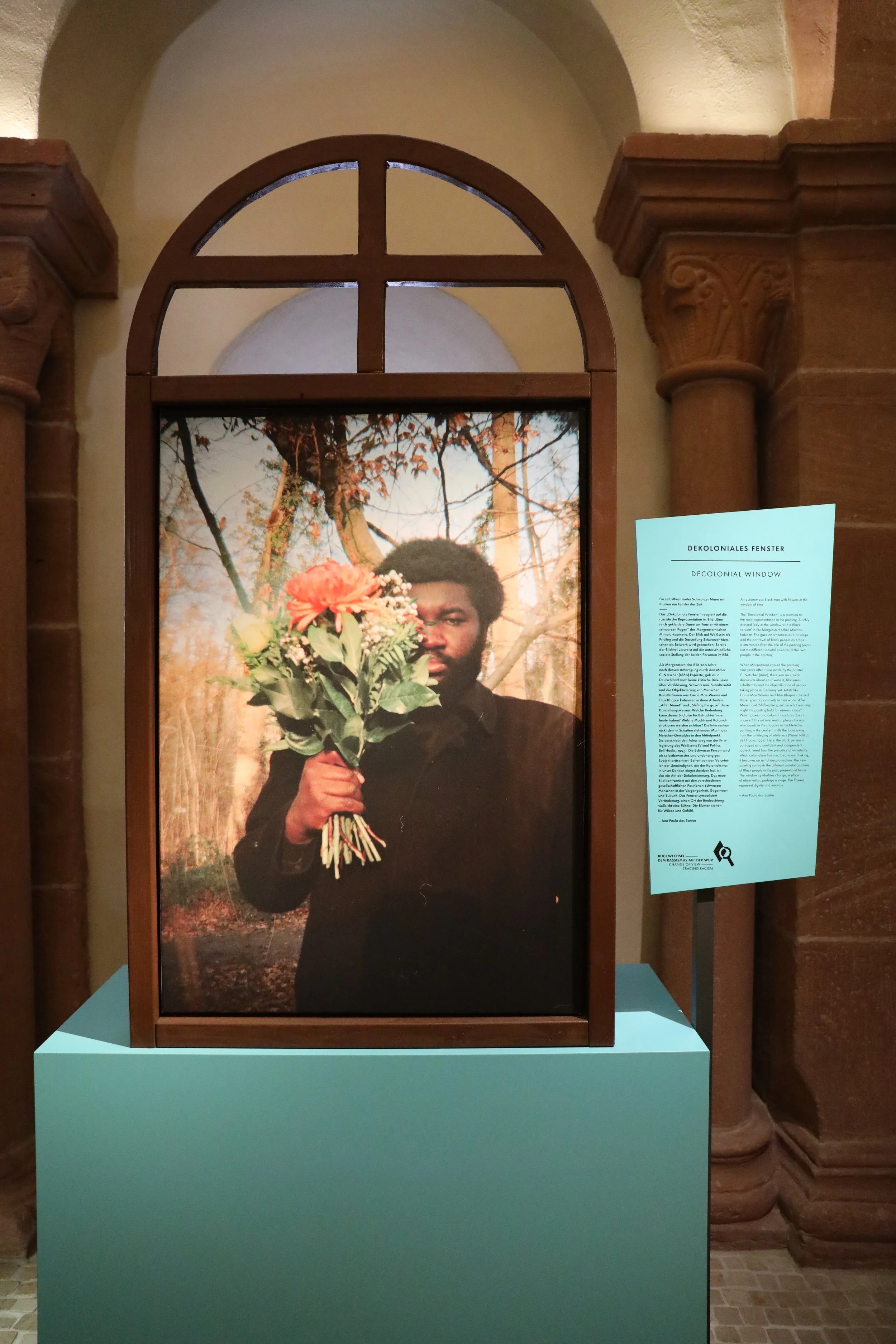

Ana Paula dos Santos, Decolonial Window - An autonomous Black man with flowers in the window of time, 2022, Installation view, The art intervention track Change of View-Tracing Racism, Historical Museum, Frankfurt am Main. Image courtesy of the artist.

Morgenstern, Morgenstern Kopie - Eine reich gekleidete Dame am Fenster mit schwarzen Pagen, 1822. The art intervention track Change of View-Tracing Racism, Historical Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Image courtesy of the artist.

Caspar Netscher, Eine reich gekleidete Dame am Fenster mit schwarzen Pagen, 1660. Image courtesy of Jean Moust

Decolonial Window -An autonomous Black man with flowers in the window of time is a photo installation by Ana Paula, part of the permanent collection at the History Museum. It is placed alongside Das Morgenstern’sche Miniaturcabinet (Morgenstern’s Miniature Cabinet) in the Staufer Chapel. A black man standing in the center of the photograph, with a bunch of flowers in his hand covering half of his face. The frame is in the shape of a window made of wood. This work is an intervention of Ana Paula on one of the Morgernstern’s miniature collection, placed on the right hand side of the third cabinet in the same room. The original work of Ana Paula’s intervention was done by Morgenstern in 1822, which is a copy of Caspar Netscher’s 1660 painting, Eine reich gekleidete Dame am Fenster mit schwarzen Pagen (A Richly Dressed Lady at the Window with a Black Servant). The title of Netscher’s work directly describes the scene depicted. In contrast, Ana Paula’s Decolonial Window- An autonomous Black man with flowers in the window of time critiques the Eurocentric narrative stemming from colonial history, particularly addressing the enslavement of Black people.

Caspar Netscher, Portrait of an Unknown Lady, with a Black Page, 1675. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts Leipzig

Around the 17th century, depicting Black servants in portraits became a trend among European aristocratic families as a way of demonstrating their wealth and status. Dutch painter Caspar Netscher actively participated early in this trend, producing several portraits. The current status of Netscher's original painting, A Richly Dressed Lady at the Window with a Black Servant, remains unclear. However, another work of his, Portrait of an Unknown Lady, with a Black Page, created in 1675 and now in the collection of the Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig (Museum of Fine Arts Leipzig), exemplifies it well.

Unlike Netscher's paintings, where the white woman is always prominently featured with her Black servant one step behind in the background, the main character in Ana Paula dos Santos's Decolonial Window - An autonomous Black man with flowers in the window of time is a Black man. This indicates a shift and diversification in the role of the storyteller. This shift is also evident in Ana Paula's participation in the exhibition Stadt der Fotografinnen, where she, as a Black Latina, becomes one of the contemporary narrators in Frankfurt am Main.

Ana Paula’s intervention on the historical works is another major body of her artistic creation apart from her black & white analog. I perceive a review also as a type of intervention of the artist’s work, but in the media of text language. I have titled this article A Trans-historical Decolonial Window, so as to create a continuity between my interpretation and the body of Ana Paula’s work. Additionally, beyond the historical colonial discourse in her work, I envision a future through her Decolonial Window - An autonomous Black man with flowers in the window of time where humanity confronts capitalism powered by machinery. Susan Sontag already said in 1977 "Needing to have reality confirmed and experience enhanced by photographs is an aesthetic consumerism to which everyone is now addicted" (6). Today, our addiction has escalated far beyond what it was half a century ago. Our reliance on social media and the flood of "pretty" photographs creates a growing gap between condensed information and physical experience. This process places our experience of connecting with the material world in serious jeopardy. Information is given to us without permission, and we often accept this unfair trade because our attention is manipulated by visual fast food, gradually allowing our minds to be controlled by technological apparatuses. Unlike any visual presence, experiences require time, effort, and a focused mind, something that was more common when we were part of the process of making. When exposed to overloaded information, cultivating focus and patience becomes even more crucial. Through the process of preparing this text by delving into Ana Paula’s work, I sense a balance. Her work provides a moment to regain authority over one's own eyes, acting as a window open to a realm of information, allowing the viewer to decide whether or not to look into it.

Ana Paula dos Santos, Decolonial Window - An autonomous Black man with flowers in the window of time, 2022, The art intervention track Change of View-Tracing Racism, Historical Museum, Frankfurt am Main. Image courtesy of the artist.

Stadt der Fotografinnen 1844-2024

(City of Women Photographers)

29/05/2024-22/09/2024

With works by Katharina Böttger, Dorothee Linnemann, Ulrike May, Christina Ramsch, Bettina Schulte Strathaus, Julie Vogel, Katharina Culié, Grete Leistikow, Jeanne Mandello, Ilse Mayer Gehrken, Ilse Bing, Emmy Limpert, Elisabeth Hase, Hannah Reck, Marta Hoepffner, Irm Schoffers, Ursula Edelmann, Laura J. Padgett, Meike Fischer, Verdiana Albano, Gisèle Freund, Ella Bergmann-Michel, Inge Werth, Erika Sulzer-Kleinemeier, Gerda Jäger-Link, Absag Tüllmann, Barbara Klemm, Mara Eggert, Annegret Soltau, Gabriele Lorenzer, Gisa Hillesheimer, Irene Peschick, Susa Templin, Christiane Feser, Sandra Mann, Ana Paula dos Santos, Lilly Lulay, Laura Schawelka, Aslı Özdemir, Wagehe Raufi

Curated by Katharina Böttger, Dorothee Linnemann, Ulrike May, Christina Ramsch, Bettina Schulte Strathaus

Frankfurt Historical Museum

Saalhof 1

60311 Frankfurt am Main

1. Richard Morrock (1973). Heritage of Strife: The Effects of Colonialist “Divide and Rule” Strategy upon the Colonized Peoples. Science & Society, 37(2), p. 130. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40401707

2. Yanofsky, N. S. (2013). The outer limits of reason: What science, mathematics, and logic cannot tell us, p. 19. MIT Press.

3. Tom Oliver (2020, March 7). The illusion of individualism helped us succeed as a species, but now the scales are tipping. Science Focus. https://www.sciencefocus.com/the-human-body/the-illusion-of-individualism-helped-us-succeed-as-a-species-but-now-the-scales-are-tipping

4. Simon, Rainald (ed.), Yijing : Chinesisch - Deutsch = Buch der Wandlungen, Stuttgart 2014.

5. Eric Otieno Sumba (2020. November 23). Frankfurt photographer Ana Paula dos Santos deconstructs A Place In The Sun in her eponymous series. Griot Magazine. Retrieved July 1, 2024, from https://griotmag.com/en/arts-photography-frankfurt-photographer-ana-paula-dos-santos-deconstructs-place-sun-series/

6. Susan Sontag (1977). On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 24.